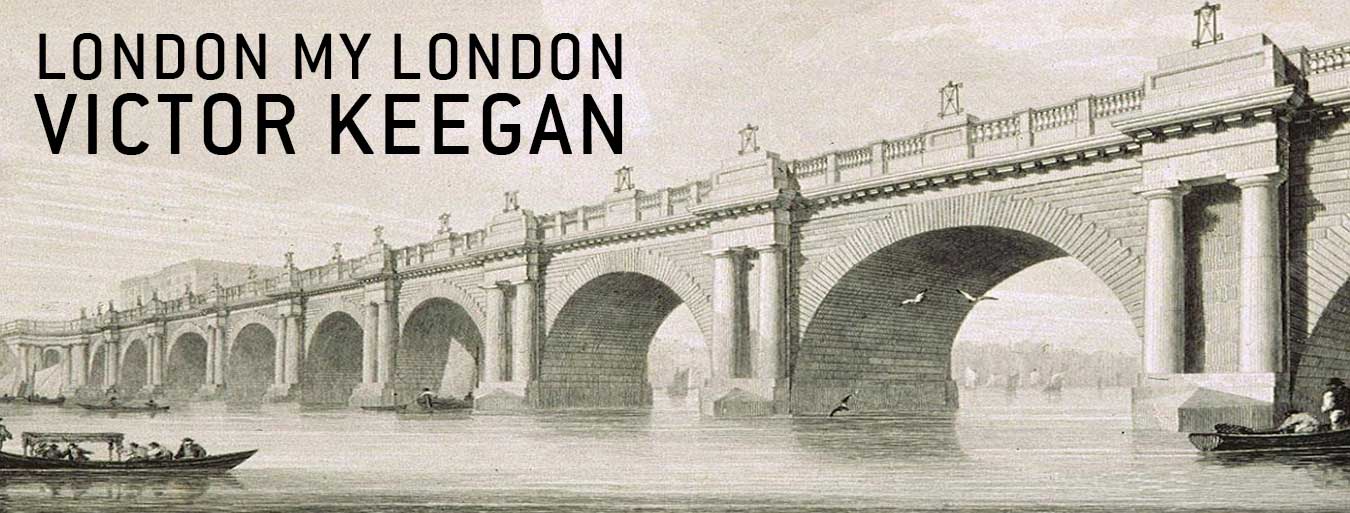

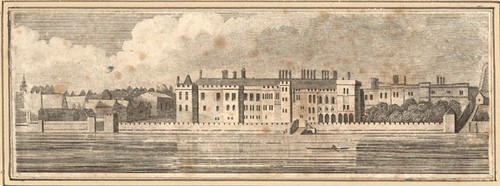

Somerset House as it was

Today’s Somerset House is a wonderful space for art and entertainment contained in a quadrangle mainly remarkable because of the paucity of its neighbours. The original, much grander, Somerset House was built by the rapacious Duke of Somerset, Lord Protector of the boy-king Edward VI (who became sovereign age 9 when Henry VIII died in 1547). He pillaged local inns, churches and other places without compensation to build his grandiose pile. He stole from buildings including the charnel house of Saint Pauls and parts of the Priory of Saint John of Jerusalem at Clerkenwell. He was only stopped from stealing stone from St Margaret’s Church adjacent to Westminster Abbey when his intentions provoked a near riot. It also provoked the intervention of Providence as Protector Somerset died before his palace was completed. Serves him right.

Somerset House was one of a series of grand palaces built along the Strand by bishops and nobility wanting to have a prestigious London pad near the Court in Whitehall. Its neighbours were Arundel House on the east and the Savoy Palace on the west. All of these palaces have now disappeared – only Somerset House, which was completely re-built by Sir William Chambers in the late 18th century, remains as a glimpse of what the north bank of Thames looked like in those days, even though Somerset House lost its river frontage when Sir Joseph Bazalgette built the Embankment.

Fascinatingly, there are still remains of the original building to be found if you know where to look – or if you are given a conducted tour as we were yesterday by Michael Trapp, Professor of Greek at Kings’ College, as part of the Arts and Humanities Festival 2014. The most dramatic remains lie under a glass floor, appropriately in the archaeological department (photo, left below). They include a Tudor wall on the left, the chalky medieval remains on the right by a bed of stones under which was uncovered a rubbish tip dating to the time when the Saxons established the Saxon trading port of Lundenwic along the Strand.

Base of walls under floor of archaeology department

Remains of an original brick wall (left) in the bike park near the door leading to the “Roman Bath”

A short distance away in the yard where Kings’ students park their bikes is a late 17th century wall (photo, right) which is the only free standing remnant of the old palace. On the other side is the entrance to what for years has been known as the Roman Bath (photo, below) partly because it was mentioned by Dickens and other authors. However, Professor Trapp has established that, although it has been used as a cold bath for periods, it was in fact a much taller structure which fed water into a spectacular fountain in the gardens of Somerset House and was nothing to do with the Romans. Another myth bites the dust.

“Roman Bath” now known to be the base of a tank feeding a fountain