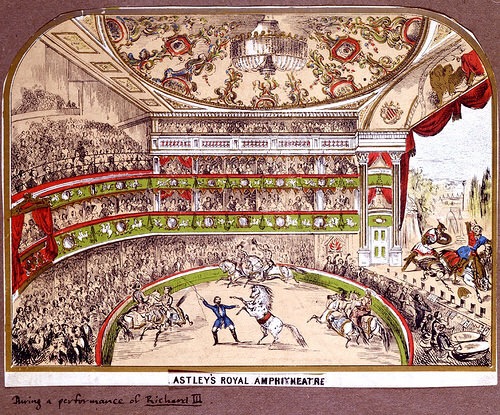

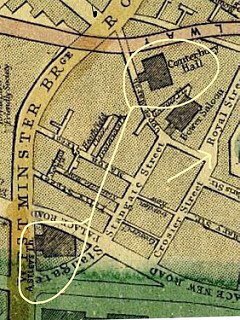

IF You stand at the junction of Royal Street and Upper Marsh in a forgotten backwater of Lambeth (see map below) you will be looking at the seedbed of two revolutions in entertainment, though there is nothing to show for it. Not even a single plaque. A few hundred yards to your left, roughly on the site of today’s Florence Nightingale Museum, stoood Astley’s the world’s first modern circus (photo below). The pioneering dimensions of its ring are still in use today. On your right a hundred yards away stood the Canterbury Music Hall. It was Britain’s – and maybe the world’s – first big music hall which spawned hundreds of imitators and to which can be traced the rise of today’s stand-up comics. The only reminder of it is the name of the apartment block which has taken its place, Canterbury House.

IF You stand at the junction of Royal Street and Upper Marsh in a forgotten backwater of Lambeth (see map below) you will be looking at the seedbed of two revolutions in entertainment, though there is nothing to show for it. Not even a single plaque. A few hundred yards to your left, roughly on the site of today’s Florence Nightingale Museum, stoood Astley’s the world’s first modern circus (photo below). The pioneering dimensions of its ring are still in use today. On your right a hundred yards away stood the Canterbury Music Hall. It was Britain’s – and maybe the world’s – first big music hall which spawned hundreds of imitators and to which can be traced the rise of today’s stand-up comics. The only reminder of it is the name of the apartment block which has taken its place, Canterbury House.

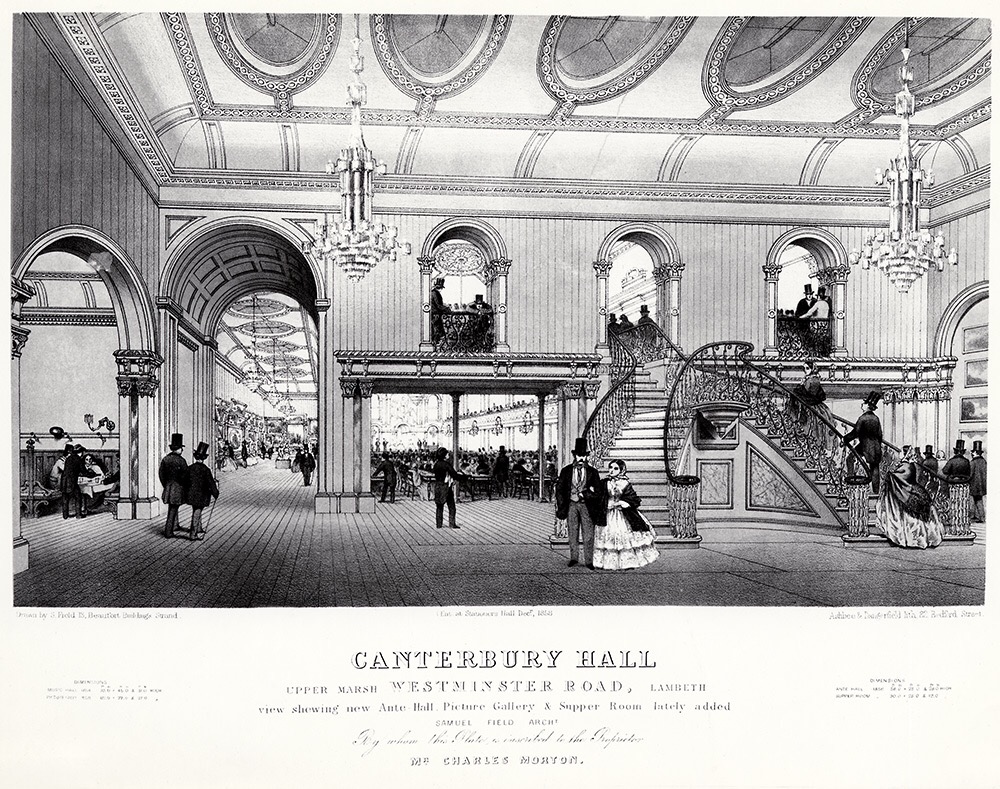

In 1849 Charles Morton opened the Canterbury Hall in an area full of gin palaces, ragged children and inebriated men. It started off in the back room of a pub. It was replaced by a larger grandiose music hall in 1856 able to take 1,500 people (and eventually double that). The 1856 theatre was built around the walls of the older version which was then demolished, reportedly, in a single weekend. Among the performers were Charlie Chaplain’s father, and numerous others including at one stage Chaplain himself. Blondin did his famous tight-rope act there. By this time it had a large entrance in Westminster Bridge Road. It also exhibited paintings and was dubbed “The Royal Academy Over the Water”. The building lasted until 1942 when it was bombed beyond restoration and demolished in 1955.

Near neighbours – Astley and Canterbury

Circuses in some form had existed for many centuries, the word itself is of Greek origin, and exhibitions of strange animals were held in ancient Egypt. But Astley’s, was the world’s first modern circus with what is now a standard circle for the ring and was born here on January 9, 1768 when Philip Astley (1742 to 1814) pioneered it as a modern arena surrounded by tiers of seats to watch trick horse riding and other acrobatic exercises, with tumblers. tight-rope walkers and clowns added later.

Astley reckoned that a diameter of 42 feet for the circus ring was needed so horses could move comfortably. Astley’s success soon spawned imitators. A rival, Charles Hughes, who had once worked with him, set up a Royal Circus a short distance from Astley’s ‘ Amphitheatre of Equestrian Arts’ in Lambeth. Hughes, who was the first to use the word “circus” in this context, took his troupe to entertain Catherine the Great in 1790 and is credited with planting the idea of circuses in Russia. Meanwhile John Rickets, another pupil of Astley, went to America and established a circus in Philadelphia. Later on, the US showman Barnum may have become more successful than Astley but there is no doubt who was the true architect of circuses. He established wooden ampitheatres around Britain and 18 in other European cities. He opened his first Paris circus in 1782 and is buried in the Pere Lachaise cemetery in Paris. Though Astley’s circus has long since disappeared he lives on in literature having been mentioned by Jane Austen, James Joyce, Charles Dickens and Tracy Chevalier.

It is one of the attractions of London that it has so much history underground often ignored. Nevertheless, at a time when Britain’s entertainment industry is doing so well it is sad that that some of the key institutions that started it all are not better remembered.