THE PHRASE “hidden gem” is the most overused way of describing curious places in London, not least by me. But in the case of the wine cellar constructed by Cardinal Wolsey – and later appropriated by Henry V111 when the Cardinal failed to get him a divorce from Catherine of Aragon – it is an understatement. It is hidden because it is concealed deep within the bowels of the huge Ministry of Defence building which straddles the east side of Whitehall needing special permission and tough security procedures to view. And it is a gem because, wow, it is the last remaining intact piece of Henry V111’s Palace of Westminster, which was once bigger – and certainly uglier – than Louis XIV’s Versailles. It was the palace of English monarchs for 200 years.

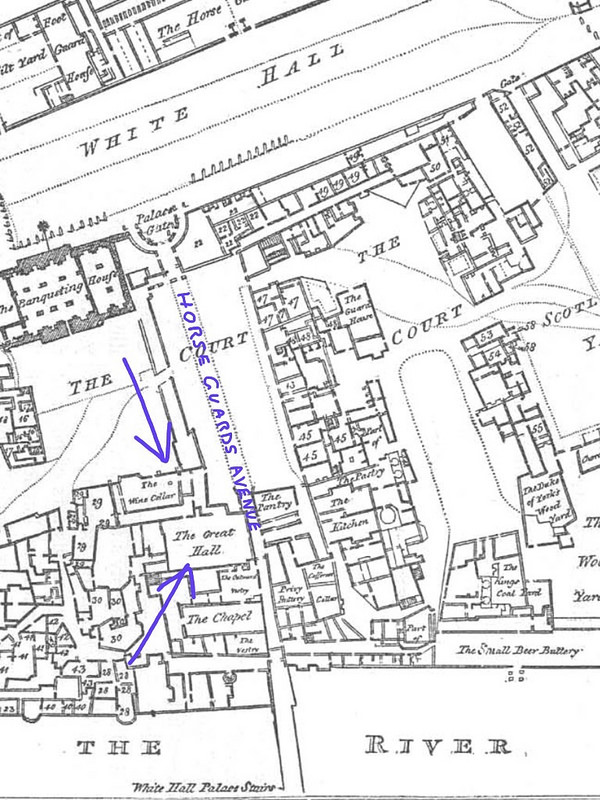

What struck me after negotiating a series of stairways was not just the unexpectedly large size of the cellar itself but the way it is presented. It is designed in museum style, with large reproductions of paintings and maps and numerous boards along the outside walls. This explains the historical background to it as you walk around the outside of a mausoleum-style structure (see, below) that has encased the cellar since it was moved sideways (10 feet to the west) in its entirety and lowered almost 19 feet during the reconstruction of the building in the 1940s. This was needed to prevent it protruding 30 feet into Horse Guards Avenue. It was an impressive bit of engineering for the time. It took 90 men eighteen months according to a parliamentary answer at the time (though the current brochure says it was completed within three months). It is a sad fact that the wine cellar was only saved because of a public outcry when the architect’s plans were revealed leading people to believe that it would be demolished.

Entering the wine cellar itself really is like falling into a time capsule. In the depths of a building where battles are planned and nuclear tactics discussed is one of the last remains of Tudor London just as it was almost 500 years ago bar a bit of restoration including replacement stones, a lick of white paint on the walls and some more recent wine barrels at each end to recreate part of the atmosphere of a bygone age. There is a stark beauty to the columns and the vaulted ceiling made of sculptured bricks which come together in “V” shapes.

Map showing proximity of the wine cellar to the Great Hall

There is bit of unfinished business. The wine cellar was very close to the Great Hall of Wolsey’s Palace where in later years some of Shakespeare’s plays were produced. I read somewhere that part of the wall of the hall can still be seen. Does anyone know?

There has been speculation about what sort of wines were stored here to slate the Cardinal’s thirst. England – and London – were not short of vineyards in those days but it is presumed that Tudor snobbery – oops, sorry, taste – would have ensured that most of the wines would have come from France including, possibly, from Champagne (which in those days was a still white wine). It is a sad fact that because of its location and the security involved it is unlikely ever to be opened to the public – unless of course, the Government sells the building off to a hotel group for re-development. On recent trends, I wouldn’t bet against that in the long term!

A memorable experience and I am most grateful to Cdr John Aitken for showing me around.

Part of the casing for the wine cellar